The state of my desk is cyclical, not unlike a menstrual cycle.

At one point, it is populated with only my computer, pencil can, notebook and snake plant. It looks like a stock photo in a Marie Kondo article. At the opposite point in the cycle, it is a repository for every bill and every project I am working on, thinking of working on, or actively avoiding until I absolutely have to deal with it. It is something like this but with more sticky notes:

Yesterday as I sat down to work, it was in just such disarray. And nothing motivates me to clean like the prospect of avoiding work, so I tackled the piles. In one, I found a white, 8x11 envelope unopened.

I knew exactly what it was.

My mom’s cousin Cyndi sent it to me just before Christmas. I’d set it aside not because I had no interest in it — quite the opposite. But because of the holidays or whatever else was scampering around in my brain then, I didn’t feel I had the capacity to give it proper attention. Now, in April, I did.

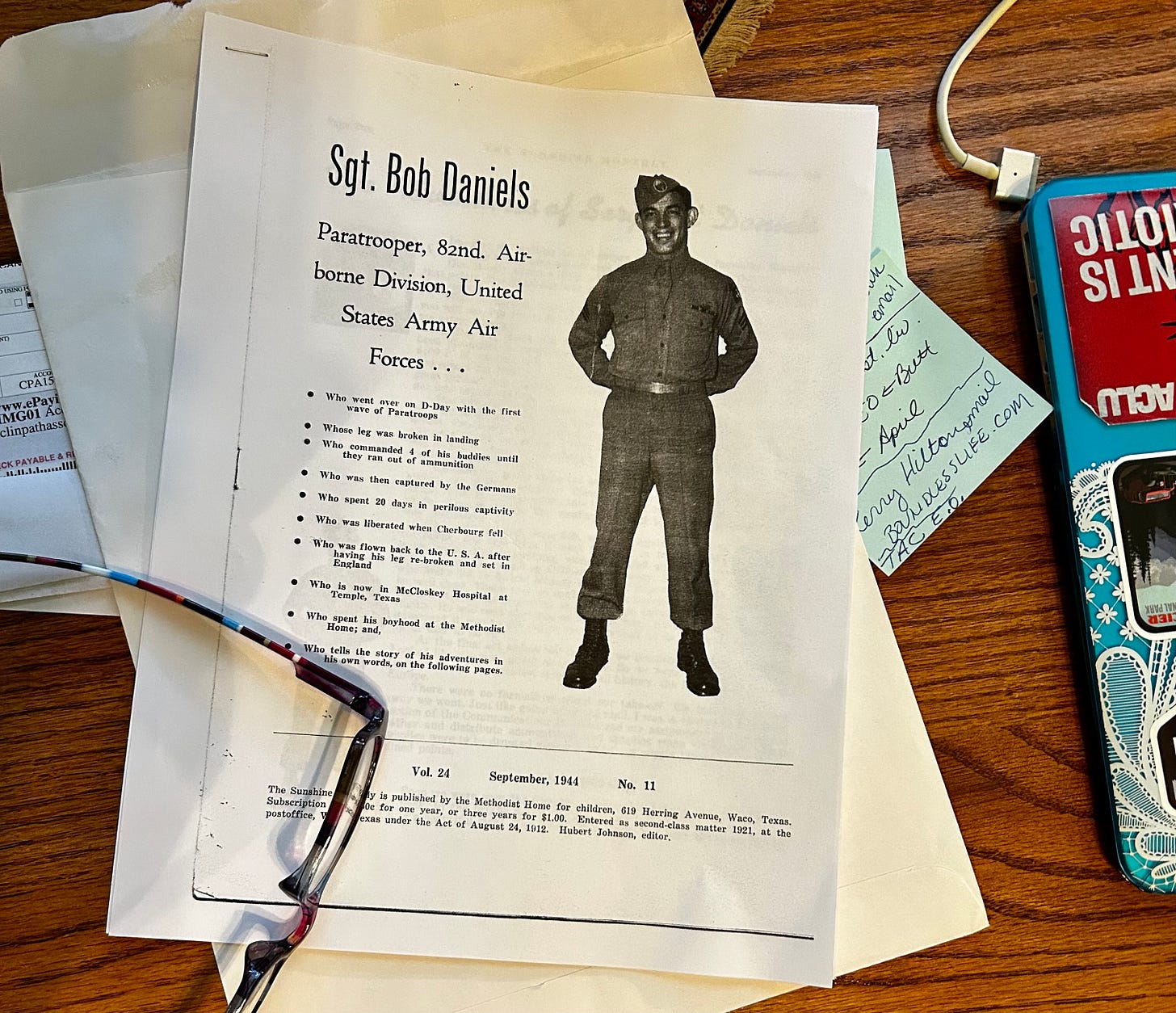

I slid carefully from the envelope Volume 24 of The Sunshine Monthly, published by the Methodist Home for Children in Waco, Texas. The date: September 1944. The black-and-white picture of an army paratrooper standing at ease with his hat cocked at a smart angle and a broad smile is Sergeant Bob Daniels, my great-uncle, my maternal grandmother’s brother, Cyndi’s father.

The story in the subsequent pages, entitled The Adventures of Sergeant Daniels, is his account of his harrowing experience dropping into Normandy as a paratrooper on D-Day. He broke his leg, having landed in a tree, but still commanded four of his men to defend their position until they ran out of ammunition. His friends escaped, but Bob, hampered by his mangled leg, was captured. He spent 20 days as a prisoner before being liberated and shipped off to England, where they re-broke and re-set his improperly healed leg. He is, in his writing at least, remarkably upbeat about all of this.

I sat at my desk, leaning closer and closer to the photocopied pages in front of me. I was engrossed in his story. I could see the planes they flew to the drop zone, their lights stretching out over the dark sky like, as Bob wrote, “a floating city.” I could feel the tension in the plane before they dropped — tension that melted when Bob cracked a joke my modern-day self didn’t get, though my shoulders relaxed as the mood lightened among the troops crowded into that airplane from which they were preparing to jump. I felt the pain in his leg when he fell and the relief of the morphine shot he self-administered before finding someone to cut him out of his tree-tangled chute. I heard the gunfire whizzing by Bob’s head as he lay, barely concealed in a shallow depression, waiting for a chance to return fire.

When I returned from 1944 wartime France to my desk in Austin in 2023, I felt fortuitousness wash over me like a wave of warmth. How lucky was I to have in my paws a first-hand account of one little corner of D-Day written by a family member? One to whom I feel a thread of connection, writer to writer. Bob wasn’t just a one-time author for The Sunshine Monthly. He’d helped run the press and regularly written some of its contents before going off to war.

There were signs of the times among those pages.

The cover notes the publication costs 50 cents for an entire year. Bob uses archaic sentence starters like “gee.” He also notes that before taking off on that historic day, “We blacked out hands and faces. Looked like we were going on the stage. So we were. Going on the stage to enact one of the greatest dramas in all history.” It is poetic and, if I’m getting his reference correctly, a nod to the racist practice of white people dressing up in blackface for entertainment.

Near the end, he lauds the Methodist Home for Children.

He and his six siblings were raised there. Bob calls it “a real home where the kids of a big family like mine can live and grow up together.” Bob was twelve when the Home took them in. As a teen who spent six years there before enlisting, I can imagine those being his honest feelings. He was one of the oldest children and likely felt the burden of responsibility for his siblings; he may have been relieved they were cared for. My grandmother, who was five when their parents died, told a different story.

The article includes photos of Uncle Bob, my grandmother, and all of the siblings between and around them. Liz, the youngest, was an infant when their mother died of complications from childbirth, and their father killed himself less than two years later — for loneliness, for the pressure of raising seven children during the Depression, for feelings of inadequacy or some other unnamed personal demons at which I can only guess.

In the family photo from 1938, the caption reads,

“Aren’t they a fine-looking group of children?”

They are, even in the grainy black-and-white photocopied images. Bob and Kitty, the oldest, stand erect and grinning in the back, the five younger ones clustered in front of them looking sweet and lovable. In the 1944 photo, six years later, their sunshiny demeanor is the same; only Betty’s smile is a bit more subdued. I lean in close again, study their faces, find my grandmother Sue and wonder what is going on behind that 14-year-old’s toothy grin. Her big brother had just returned from the war; I’m sure she was relieved and proud. From her accounts to me as her grandchild decades later, however, those were not particularly happy years for her. Despite the Home’s stance that they were indeed a home and not an orphanage, my grandmother felt like an orphan.

I can contemplate a lot of reasons Sue and Bob have disparate views of the Home.

Their ages, their genders and perhaps their different personalities played a role in how the world treated them. My grandmother was five and in less of a position to process the loss of her parents than Bob was, having the older brain. Not to say it must’ve been easy on a twelve-year-old to lose his parents. As a girl in 1944, my grandmother’s stories indicate she felt less valuable than her brothers.

Sue was also a firebrand of a personality, not to be squashed, so I’m sure that prompted some of the adults at the Home to try all the harder to squash her. Bob was a war hero. And if I can read anything into his war account about who he was, I’d guess he was one of those people who can let trauma roll off his back, his core remaining untouched. He writes of D-Day as an incredible adventure and does not dwell on the fear and dread of being a prisoner anymore than he does the excruciating pain of an untreated broken leg.

I didn’t know Bob personally, though, so I can only guess with the clues he’s left behind. Perhaps that “war as a great adventure” approach is indicative of the times; there wasn’t a big market for musings on PTSD in 1944. Or maybe it really is who he was. I have my grandmother’s stories and the trauma they caused — emotional difficulties she never admitted to but that I can infer by the frequency and tone with which she told certain tales.

I cherish these pages Cyndi has sent me.

I even relish her handwritten note apologizing for the delay in sending them — the treasured family story it took me four months to unearth from my desk and appreciate. They are a link to my ancestors, perhaps a window into where my penchant for writing comes from — a talent my grandmother also shared. She wrote at a messy desk tucked into the closet of a back room in her house and had a sign tacked up that read, “A clean, uncluttered desk is the sign of a sick mind.”

Bob’s story is a unique account of one person’s dramatic experience in a worldwide conflict. And the pages are a reminder of perspective, of how two people in the same family can be raised in the same environment with the same caregivers and have entirely different takes on the matter. Both are true, and I will hold both with equal reverence for those who came before me.

I love this April! Thanks SO much.

Great Piece / Article April !! ___I met (and remember well, due to his wit and very positive attitude...) Bob in October , 1986 --- when he married my brother David Wood and Valerie White. _____:)